if marginal cost increases what happens to the average cost

Effigy 1: Marginal and Total Cost of Production

In economic science, the marginal cost is the change in the total cost that arises when the quantity produced is incremented, the toll of producing additional quantity.[i] In some contexts, information technology refers to an increment of one unit of output, and in others it refers to the rate of change of total price as output is increased by an minute amount. As Effigy 1 shows, the marginal cost is measured in dollars per unit, whereas total cost is in dollars, and the marginal toll is the slope of the total price, the rate at which it increases with output. Marginal cost is different from average toll, which is the full toll divided by the number of units produced.

At each level of production and time period being considered, marginal cost include all costs that vary with the level of production, whereas costs that exercise non vary with product are fixed. For example, the marginal cost of producing an motorcar will include the costs of labor and parts needed for the additional car but non the stock-still cost of the factory building that exercise not change with output. The marginal cost can exist either brusque-run or long-run marginal cost, depending on what costs vary with output, since in the long run even building size is called to fit the desired output.

If the cost function is continuous and differentiable, the marginal toll is the first derivative of the cost function with respect to the output quantity :[2]

If the price function is non differentiable, the marginal price can be expressed as follows:

where denotes an incremental alter of 1 unit.

Brusque run marginal price [edit]

Brusque run marginal cost is the change in total price when an additional output is produced in the short run and some costs are fixed. On the right side of the page, the brusque-run marginal toll forms a U-shape, with quantity on the x-axis and toll per unit on the y-axis.

On the short run, the firm has some costs that are fixed independently of the quantity of output (e.g. buildings, machinery). Other costs such as labor and materials vary with output, and thus show up in marginal cost. The marginal cost may offset decline, as in the diagram, if the additional cost per unit is loftier if the business firm operates at too low a level of output, or it may start flat or ascent immediately. At some point, the marginal cost rises as increases in the variable inputs such equally labor put increasing pressure on the fixed assets such as the size of the building. In the long run, the house would increase its stock-still assets to correspond to the desired output; the short run is defined as the period in which those assets cannot exist changed.

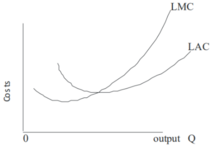

Long run marginal cost [edit]

The long run is divers as the length of time in which no input is stock-still. Everything, including edifice size and mechanism, can be chosen optimally for the quantity of output that is desired. As a event, even if short-run marginal toll rises because of capacity constraints, long-run marginal price can be constant. Or, there may exist increasing or decreasing returns to calibration if technological or management productivity changes with the quantity. Or, at that place may be both, as in the diagram at the correct, in which the marginal cost first falls (increasing returns to scale) and so rises (decreasing returns to scale).[3]

Cost functions and relationship to average toll [edit]

In the simplest case, the total cost part and its derivative are expressed as follows, where Q represents the production quantity, VC represents variable costs, FC represents stock-still costs and TC represents total costs.

Fixed costs represent the costs that do non change every bit the product quantity changes. Fixed costs are costs incurred by things similar hire, building space, machines, etc. Variable costs alter equally the production quantity changes, and are ofttimes associated with labor or materials. The derivative of stock-still price is zero, and this term drops out of the marginal price equation: that is, marginal cost does not depend on fixed costs. This can exist compared with average full price (ATC), which is the total cost (including fixed costs, denoted C0) divided by the number of units produced:

For detached calculation without calculus, marginal cost equals the change in full (or variable) cost that comes with each additional unit produced. Since fixed cost does not change in the short run, it has no result on marginal cost.

For case, suppose the total price of making 1 shoe is $30 and the full price of making ii shoes is $40. The marginal cost of producing shoes decreases from $30 to $10 with the production of the second shoe ($40 – $xxx = $ten).

Marginal cost is non the toll of producing the "adjacent" or "last" unit of measurement.[4] The cost of the last unit is the same equally the toll of the start unit and every other unit of measurement. In the short run, increasing product requires using more of the variable input — conventionally assumed to be labor. Calculation more labor to a fixed upper-case letter stock reduces the marginal product of labor because of the diminishing marginal returns. This reduction in productivity is not limited to the additional labor needed to produce the marginal unit – the productivity of every unit of labor is reduced. Thus the cost of producing the marginal unit of output has 2 components: the cost associated with producing the marginal unit of measurement and the increment in average costs for all units produced due to the "harm" to the entire productive process. The showtime component is the per-unit or average cost. The second component is the small increase in price due to the law of diminishing marginal returns which increases the costs of all units sold.

Marginal costs can also exist expressed as the cost per unit of labor divided by the marginal product of labor.[5] Cogent variable cost as VC, the constant wage rate equally w, and labor usage as L, we have

Here MPL is the ratio of increase in the quantity produced per unit increase in labour: i.east. ΔQ/ΔL, the marginal product of labor. The concluding equality holds because is the modify in quantity of labor that brings about a i-unit change in output.[6] Since the wage charge per unit is assumed abiding, marginal cost and marginal product of labor have an inverse human relationship—if the marginal product of labor is decreasing (or, increasing), then marginal price is increasing (decreasing), and AVC = VC/Q=wL/Q = w/(Q/50) = w/AP50

Empirical data on marginal cost [edit]

While neoclassical models broadly assume that marginal cost will increase as product increases, several empirical studies conducted throughout the 20th century have ended that the marginal toll is either constant or falling for the vast majority of firms.[seven] Nearly recently, sometime Federal Reserve Vice-Chair Alan Blinder and colleagues conducted a survey of 200 executives of corporations with sales exceeding $10 meg, in which they were asked, among other questions, virtually the structure of their marginal cost curves. Strikingly, simply 11% of respondents answered that their marginal costs increased as production increased, while 48% answered that they were constant, and 41% answered that they were decreasing.[8] : 106 Summing up the results, they wrote:

...many more than companies country that they take falling, rather than ascension, marginal price curves. While there are reasons to wonder whether respondents interpreted these questions about costs correctly, their answers paint an image of the toll structure of the typical firm that is very dissimilar from the one immortalized in textbooks.

— Request Well-nigh Prices: A New Approach to Understanding Cost Stickiness, p. 105[8]

Many Post-Keynesian economists have pointed to these results as evidence in favor of their own heterodox theories of the house, which generally assume that marginal price is abiding as production increases.[7]

Economies of scale [edit]

Economies of calibration apply to the long run, a bridge of time in which all inputs can be varied by the house then that there are no stock-still inputs or fixed costs. Production may be subject to economies of scale (or diseconomies of scale). Economies of scale are said to exist if an boosted unit of output can be produced for less than the boilerplate of all previous units – that is, if long-run marginal toll is below long-run average cost, so the latter is falling. Conversely, at that place may exist levels of product where marginal price is higher than boilerplate cost, and the boilerplate cost is an increasing function of output. Where there are economies of scale, prices set up at marginal cost volition fail to cover full costs, thus requiring a subsidy.[9] For this generic case, minimum average cost occurs at the point where average cost and marginal price are equal (when plotted, the marginal toll curve intersects the average cost bend from beneath).

Perfectly competitive supply curve [edit]

The portion of the marginal cost curve higher up its intersection with the average variable cost curve is the supply curve for a firm operating in a perfectly competitive market (the portion of the MC curve below its intersection with the AVC curve is not part of the supply curve considering a business firm would not operate at a toll beneath the shutdown point). This is not true for firms operating in other market structures. For example, while a monopoly has an MC curve, it does non take a supply curve. In a perfectly competitive market, a supply curve shows the quantity a seller is willing and able to supply at each toll – for each price, there is a unique quantity that would be supplied.

Decisions taken based on marginal costs [edit]

In perfectly competitive markets, firms determine the quantity to be produced based on marginal costs and sale cost. If the auction cost is higher than the marginal cost, so they produce the unit and supply information technology. If the marginal price is higher than the price, it would not be profitable to produce it. So the production will be carried out until the marginal cost is equal to the sale price.[ten]

Relationship to stock-still costs [edit]

Marginal costs are not affected by the level of fixed price. Marginal costs can be expressed as ∆C/∆Q. Since fixed costs practice not vary with (depend on) changes in quantity, MC is ∆VC/∆Q. Thus if fixed cost were to double, the marginal toll MC would not be affected, and consequently, the profit-maximizing quantity and price would non change. This can be illustrated by graphing the short run full cost curve and the short-run variable cost curve. The shapes of the curves are identical. Each curve initially increases at a decreasing rate, reaches an inflection point, then increases at an increasing rate. The only difference between the curves is that the SRVC curve begins from the origin while the SRTC bend originates on the positive part of the vertical centrality. The altitude of the beginning bespeak of the SRTC above the origin represents the fixed price – the vertical distance betwixt the curves. This distance remains abiding as the quantity produced, Q, increases. MC is the slope of the SRVC curve. A change in stock-still cost would be reflected by a change in the vertical distance between the SRTC and SRVC curve. Any such alter would have no consequence on the shape of the SRVC curve and therefore its slope MC at whatsoever point. The irresolute law of marginal toll is similar to the changing law of average price. They are both decrease at offset with the increase of output, then start to increase after reaching a sure calibration. While the output when marginal cost reaches its minimum is smaller than the average total price and boilerplate variable toll. When the average total cost and the average variable cost reach their lowest point, the marginal price is equal to the boilerplate cost.

[edit]

Of great importance in the theory of marginal cost is the distinction between the marginal private and social costs. The marginal private cost shows the toll borne by the business firm in question. Information technology is the marginal private cost that is used by business decision makers in their profit maximization behavior. Marginal social cost is like to private cost in that it includes the cost of private enterprise but also any other cost (or offsetting benefit) to parties having no direct association with purchase or sale of the production. It incorporates all negative and positive externalities, of both production and consumption. Examples include a social price from air pollution affecting third parties and a social benefit from flu shots protecting others from infection.

Externalities are costs (or benefits) that are not borne past the parties to the economical transaction. A producer may, for example, pollute the surroundings, and others may deport those costs. A consumer may consume a proficient which produces benefits for society, such as education; considering the individual does not receive all of the benefits, he may eat less than efficiency would suggest. Alternatively, an individual may be a smoker or alcoholic and impose costs on others. In these cases, production or consumption of the adept in question may differ from the optimum level.

Negative externalities of product [edit]

Negative Externalities of Production

Much of the time, private and social costs do not diverge from one another, merely at times social costs may be either greater or less than private costs. When the marginal social cost of production is greater than that of the individual cost function, at that place is a negative externality of production. Productive processes that outcome in pollution or other environmental waste are textbook examples of production that creates negative externalities.

Such externalities are a result of firms externalizing their costs onto a third political party in society to reduce their own total cost. As a result of externalizing such costs, nosotros meet that members of society who are not included in the firm will exist negatively afflicted by such behavior of the firm. In this example, an increased cost of production in society creates a social toll curve that depicts a greater cost than the private price bend.

In an equilibrium state, markets creating negative externalities of production will overproduce that expert. Equally a result, the socially optimal product level would be lower than that observed.

Positive externalities of production [edit]

Positive Externalities of Product

When the marginal social toll of product is less than that of the private cost role, at that place is a positive externality of production. Product of public appurtenances is a textbook example of production that creates positive externalities. An example of such a public good, which creates a divergence in social and private costs, is the production of education. Information technology is oftentimes seen that pedagogy is a positive for whatever whole society, also every bit a positive for those direct involved in the market.

Such production creates a social cost curve that is below the private price bend. In an equilibrium state, markets creating positive externalities of production volition underproduce their adept. As a result, the socially optimal product level would be greater than that observed.

Relationship betwixt marginal cost and boilerplate total cost [edit]

The marginal price intersects with the boilerplate total toll and the boilerplate variable cost at their lowest betoken. Take the [Human relationship between marginal toll and average total cost] graph equally a representation.

Relationship between marginal toll and average total cost

Say the starting indicate of level of output produced is north. Marginal toll is the change of the total cost from an additional output [(n+1)thursday unit]. Therefore, (refer to "Boilerplate cost" labelled picture on the right side of the screen.

In this case, when the marginal cost of the (n+1)thursday unit of measurement is less than the average price(northward), the average cost (n+one) will go a smaller value than average cost(n). It goes the opposite fashion when the marginal toll of (n+1)thursday is higher than average cost(n). In this case, The average cost(north+one) will be higher than average price(due north). If the marginal cost is plant lying under the boilerplate price curve, it will bend the boilerplate toll bend down and if the marginal cost is to a higher place the boilerplate toll curve, information technology will bend the average cost curve upwards. You tin see the table above where before the marginal cost curve and the average cost curve intersect, the boilerplate price bend is downwards sloping, withal afterwards the intersection, the average cost bend is sloping upwards. The U-shape graph reflects the law of diminishing returns. A firm can only produce then much merely later the production of (due north+1)th output reaches a minimum toll, the output produced afterwards will just increase the average total price (Nwokoye, Ebele & Ilechukwu, Nneamaka, 2018).

Turn a profit maximization [edit]

The profit maximizing graph on the right side of the page represents optimal production quantity when both The marginal cost and the marginal profit line intercepts. The Blackness line represents the intersection where the profits are the greatest ( Marginal revenue = marginal toll). The left side of the black vertical line marked as "profit-maximising quantity" is where the marginal revenue is larger than marginal cost. If a business firm sets its product on the left side of the graph and decides to increase the output, the additional revenue per output obtained will exceed the boosted cost per output. From the "profit maximizing graph", we could discover that the acquirement covers both bar A and B, meanwhile the cost only covers B. Of form A+B earns yous a profit but the increase in output to the point of MR=MC yields extra turn a profit that can cover the revenue for the missing A. The firm is recommended to increase output to reach (Theory and Applications of Microeconomics, 2012).

On the other mitt, the right side of the black line (Marginal revenue = marginal toll), shows that marginal cost is more than marginal revenue. Suppose a firm sets its output on this side, if it reduces the output, the cost will subtract from C and D which exceeds the subtract in revenue which is D. Therefore, decreasing output until the point of (marginal revenue=marginal cost) will lead to an increase in profit (Theory and Applications of Microeconomics, 2012).

See too [edit]

- Boilerplate cost

- Break even analysis

- Toll

- Cost curve

- Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis

- Cost-sharing mechanism

- Economic surplus

- Marginal concepts

- Marginal factor cost

- Marginal production of labor

- Marginal revenue

- Merit goods

References [edit]

- ^ O'Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003). Economics: Principles in Action . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 111. ISBN0-13-063085-3.

- ^ Simon, Carl; Blume, Lawrence (1994). Mathematics for Economists. West. W. Norton & Visitor. ISBN0393957330.

- ^ The classic reference is Jakob Viner, "Price Curves and Supply Curve," Zeitschrift fur Nationalokonomie, iii:23-46 (1932).

- ^ Silberberg & Suen, The Structure of Economic science, A Mathematical Analysis tertiary ed. (McGraw-Loma 2001) at 181.

- ^ Come across http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/economic science/14-01-principles-of-microeconomics-autumn-2007/lecture-notes/14_01_lec13.pdf.

- ^ Chia-Hui Chen, course materials for 14.01 Principles of Microeconomics, Fall 2007. MIT OpenCourseWare (http://ocw.mit.edu), Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Downloaded on [12 Sept 2009].

- ^ a b Lavoie, Marc (2014). Post-Keynesian Economics: New Foundations. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. p. 151. ISBN978-i-84720-483-7.

- ^ a b Blinder, Alan S.; Canetti, Elie R. D.; Lebow, David E.; Rudd, Jeremy B. (1998). Asking About Prices: A New Approach to Understanding Cost Stickiness. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. ISBN0-87154-121-1.

- ^ Vickrey W. (2008) "Marginal and Average Cost Pricing". In: Palgrave Macmillan (eds) The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London[ ISBN missing ]

- ^ "Piana 5. (2011), Refusal to sell – a central concept in Economics and Management, Economics Web Found."

External links [edit]

- Bio, Full (2021-05-19). "Marginal Cost Of Production Definition". Investopedia . Retrieved 2021-05-28 .

- Nwokoye, Ebele Stella; Ilechukwu, Nneamaka (2018-08-06). "CHAPTER V THEORY OF COSTS". ResearchGate . Retrieved 2021-05-28 .

- "Theory and Applications of Microeconomics - Tabular array of Contents". 2012 Book Archive. 2012-12-29. Retrieved 2021-05-28 .

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marginal_cost

0 Response to "if marginal cost increases what happens to the average cost"

Postar um comentário